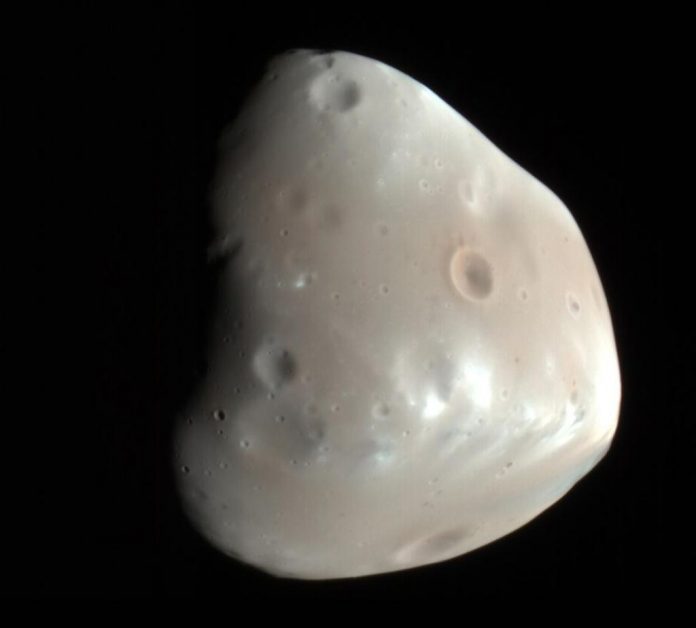

Scientists from the SETI Institute and Purdue University have found that the only way to produce Deimos’s unusually tilted orbit is for Mars to have had a ring billions of years ago. While some of the more massive planets in our solar system have giant rings and numerous big moons, Mars only has two small, misshapen moons, Phobos and Deimos. Although these moons are small, their peculiar orbits hide important secrets about their past.

For a long time, scientists believed that Mars’s two moons, discovered in 1877, were captured asteroids. However, since their orbits are almost in the same plane as Mars’s equator, that the moons must have formed at the same time as Mars. But the orbit of the smaller, more distant moon Deimos is tilted by two degrees.

“The fact that Deimos’s orbit is not exactly in plane with Mars’s equator was considered unimportant, and nobody cared to try to explain it,” says lead author Matija Ćuk, a research scientist at the SETI Institute. “But once we had a big new idea and we looked at it with new eyes, Deimos’s orbital tilt revealed its big secret.”

This significant new idea was put forward in 2017 by Ćuk’s co-author David Minton, professor at Purdue University and his then-graduate student Andrew Hesselbrock. Hesselbrock and Minton noted that Mars’s inner moon, Phobos, is losing height as its tiny gravity is interacting with the looming Martian globe. Soon, in astronomical terms, Phobos’s orbit will drop too low, and Mars’s gravity will pull it apart to make a ring around the planet. Hesselbrock and Minton proposed that over billions of years, generations of Martian moons were destroyed into rings. Each time, the ring would then give rise to a new, smaller moon to repeat the cycle over again.

This cyclic Martian moon theory has one crucial element that makes Deimos’s tilt possible: a newborn moon would move away from the ring and Mars. Which is in the opposite direction from the inward spiral Phobos is experiencing due to gravitational interactions with Mars. An outward-migrating moon just outside the rings can encounter a so-called orbital resonance, in which Deimos’s orbital period is three times that of the other moon.

These orbital resonances are picky but predictable about the direction in which they are crossed. We can tell that only an outward-moving moon could have strongly affected Deimos, which means that Mars must have had a ring pushing the inner moon outward. Ćuk and collaborators deduce that this moon may have been 20 times as massive as Phobos, and may have been its “grandparent” existing just over 3 billion years ago, which was followed by two more ring-moon cycles, with the latest moon being Phobos.

This insight from a modest tilt of a humble moon’s orbit has some significant consequences for our understanding of Mars and its moons. The discovery of the past orbital resonance all but clinches the cyclic ring-moon theory for Mars. It implies that for much of its history, Mars possessed a prominent ring. While Deimos is billions of years old, Ćuk and collaborators believe Phobos is young as astronomical objects go, forming maybe only 200 million years ago, just in time for the dinosaurs.

These theories may be up for some serious testing in a few years, as Japanese space agency JAXA plans to send a spacecraft to Phobos in 2024, which would collect samples from the moon’s surface and bring them back to Earth. Ćuk is hopeful that this will give us firm answers about the murky past of the Martian moons: “I do theoretical calculations for a living, and they are good, but getting them tested against the real world now and then is even better.”

This research is presented at the 236th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, held virtually on June 1-3, 2020, and is accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.