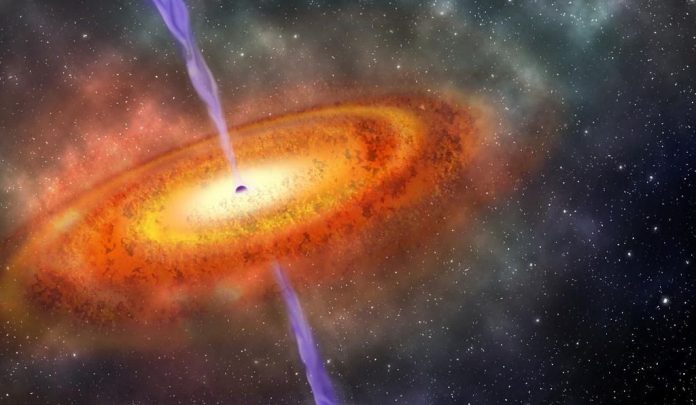

Scientists have just discovered a supermassive black hole that existed surprisingly early in the history of the universe, and the puzzling find is shedding new light on when the first stars blinked on.

A team of scientists announced their analysis of this quasar J1342+0928 today. The remarkable object originates from an era when the Universe looked very different than it does today. Its discovery could shed light, both literally and figuratively, on the origin story of the neophyte cosmos.

“By analysing this one object, we learn about the formation and growth of the first black holes, the production of dust in the galaxy hosting the black hole and about the Universe itself when it was only five percent of its current age,” Bram Venemans, researcher at the Max Plack Institute for Astronomy told lintelligencer.

The ancient Universe has a complex story. Right after the Big Bang, the Universe became completely opaque as light bounced and scattered off of the particles in the hot plasma of unpaired protons and electrons. Somewhere around 400,000 years later, these particles bound together and the light could travel unimpeded, eventually reaching our telescopes. Scientists observe this ancient light as microwaves hitting Earth from all directions—it’s called the cosmic microwave background. After that came a period where the Universe had lots of neutral hydrogen which emitted no light, called the Dark Ages.

A few hundred million years later, stuff began to glow as atoms condensed and released energy once again—including this quasar. “How that process happened and when exactly it happened has profound implications to how the Universe evolved afterwards,” Eduardo Bañados from the The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science told lintelligencer.

The team noticed this quasar in a search through three surveys of the sky, then followed up with more specific probing from tools like spectrographs and radio telescopes. That way, they could determine properties like the object’s mass and age, and determine the potential rate at which such a galaxy with this object at the center could produce stars.

They also noticed a signature of missing spectral lines—missing colors in the spectrum of light unleashed by the quasar likely caused by interactions with the neutral hydrogen of this “reionization” period Bañados described.

Daniel Mortlock from Imperial College London pointed out that the reonization conclusion is based on some modeling assumptions in an email to lintelligencer. However, it was “overall, a great discovery,” he said. He felt it unambiguously proved the identity and age of the object, 80 million years older than the previous most distant quasar. He felt it would help scientists better study black hole formations and the conditions of the early Universe.

There’s more work to do, of course. Bañados said that with one single black hole there are few conclusions to be made. Venemans said there’s still much to learn about the dust itself, and that the size of the object couldn’t be determined.

But with a distant light so bright, the team hopes to learn more using powerful new telescopes like the Atacama Large Millimeter Array in Chile and the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope. Bañados said: “This object is so luminous that it will be the subject of future studies where more surprises might come.”