From schools of fish, to herds of antelope and even human societies, one of the group’s many advantages is its inherent safety. Surrounded by their peers, individuals can lower their vigilance and calmly engage in other activities, such as foraging, or watching YouTube videos.

But the Safety in Numbers rule has more to it than just being together. In many cases, communication also plays a big role. Social cues of danger are fairly well known. Just think about the different ways animals use to convey the presence of a threat. Shrieks, yelps, and barks immediately come to mind.

Now, how about naming a few examples of social cues of safety? After all, knowing that the danger has passed is important for lowering one’s defenses and resuming other activities. The reason this task is more challenging is because it’s actually a trick question—no social safety cues have been identified until now.

Remarkably, the discovery of the first social safety cue was made thanks to a tiny insect: the fruit fly. These results, published Aug. 21 2020 in the scientific journal Nature Communications, mark a new phase in our understanding of how social communication works.

A silent sign of danger

“When people think about social communication of danger, they normally think about alarm calls,” says Marta Moita, a principal investigator at the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown in Portugal. “But we are interested in a different type of threat cue, the expression of the defensive behaviors themselves.”

Freezing is one of the three universal defense responses, together with fight and flight. This response is the best course of action in situations where escape is either impossible or less advantageous than just staying still with the hope of remaining unnoticed.

“Freezing may actually be a safer way of conveying the existence of danger to others,” Moita points out. “This manner of social communication does not require the active production of a signal that may result in drawing unwelcome attention. Also, freezing may constitute a public cue that can be used by any surrounding animal regardless of species,” she explains.

Moita’s team has recently demonstrated that individual fruit flies freeze in response to an inescapable threat. This finding triggered their curiosity, would this behavior change if there other flies were around?

Safety in (exactly how many) numbers

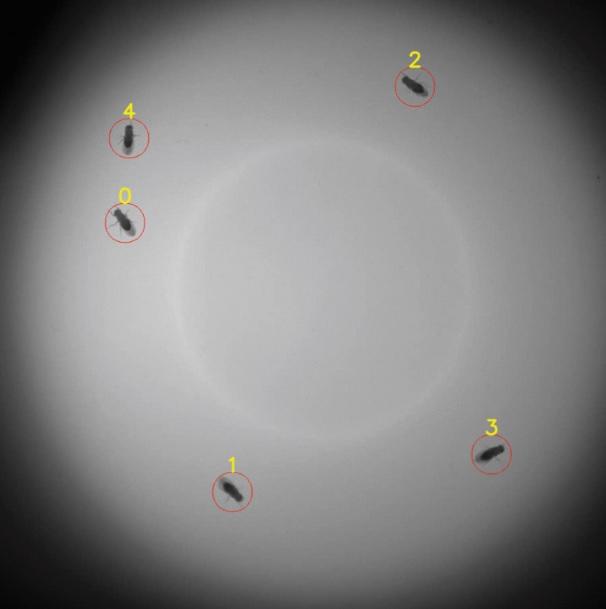

To answer this question, Clara Ferreira, the lead author of the study, proceeded with a systematic set of experiments, beginning with one fly, then two, three, and so forth, up to groups of ten.

“We placed the flies in a transparent closed chamber and repeatedly exposed them to an expanding dark disc, which mimics an object on a collision course. Just imagine the visual effect of an approaching open palm,” Ferreira explains. “Many visual animals that are exposed to such a stimulus respond defensively, including humans. If they freeze, they often stay motionless for quite some time, even after the threat is gone.”

Their results revealed that group size matters. “All groups—from two to ten—froze less than individual flies. However, we were surprised to find a complex effect of group size on the flies’ behavior,” says Ferreira.

In groups of six and more, the flies froze transiently when the threat appeared and then resumed movement once it was gone. On the other hand, the flies’ response pattern in groups of five or less was more similar to that of individual flies.

“Flies in those groups still froze less than single flies. However, their freezing time increased as the experiment progressed. The more repetitions of the threatening stimulus they experienced, the longer they would remain motionless when it reappeared,” Ferreira explains. “These results were very intriguing,” she adds. “This was the first time the effect of group size on freezing was systematically characterized in any species and it revealed a fascinating and intricate relation.”

Should I stay or should I go?

These findings clearly demonstrated that flies change their defensive responses when others are present. This novel observation raised a pressing question—what social cues were the flies responding to? To find the answer, Ferreira and Moita meticulously analyzed their previous results and conducted additional experiments using blind flies and controllable magnetic “dummy flies.”

The results revealed a two-part answer. “The first part describes the flies’ response to the appearance of the threat,” Ferreira recounts. “We learned that an individual fly was more likely to enter freezing if its peers (magnetic or otherwise) froze in response to the threat. We were somewhat expecting to see this. Previous studies in the lab showed that in specific situations, freezing is a social cue of danger in rats. Here, we witnessed a similar behavior in flies.”

The second part of the answer, however, caught the researchers by surprise: flies were more likely to exit freezing if others began to move. “This means that flies were using the resumption of movement as a social cue of safety!,” Ferreira points out.

“This is a completely novel phenomenon,” Moita adds. “There are many types of recorded social alarm cues, but this is the first social safety cue to be identified in any animal species. It also pins down movement as the social cue we were searching for. In a sense, this cue ‘kills two birds with one stone’: the sudden cessation of movement signifies danger, whereas its resumption signifies safety.”

Next stop—the brain

Moita and Ferreira’s series of striking discoveries opens a unique opportunity to learn how the brain perceives and responds to social cues. “The fruit fly is one of the most powerful animal models used in scientific research nowadays,” says Ferreira. “It offers specialized tools to study neurobiology in a very specific and targeted manner.”

Indeed, the authors have already begun unraveling the neural basis of this behavior. “In this project, we identified a set of visual neurons that are crucial for perceiving the movement of others as a safety cue,” Ferreira explains. “And we are planning to continue investigating the neural circuits involved.”

As Moita points out, even though flies and humans are different, there are parallels across these and other species that may make findings in the fly relevant for revealing general principles. “Since we are studying a fundamental behavior spanning almost all of animal life—the tendency to seek safety in numbers—we believe that our work paves the way for understanding conserved mechanisms in other animals,” she concludes.