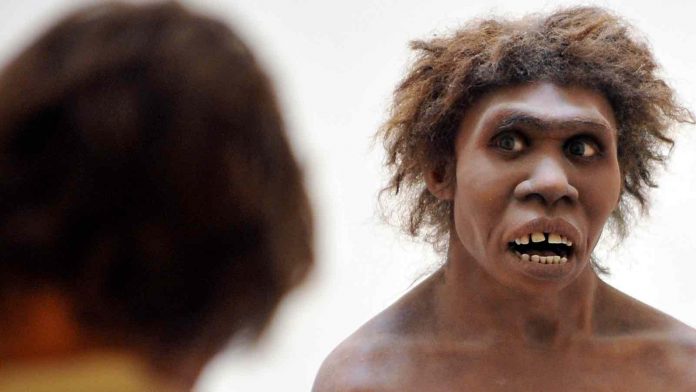

We humans like to think we’re the cream of the crop when it comes to animal life on Earth, but the truth is we’re all a bunch of mutts. Many of our ancient ancestors mingled with Neanderthals, and the telltale signs of that “mingling” are still present in our DNA today. We didn’t know that many humans had Neanderthal genetic code floating around in their bodies until about a decade ago, but new research is helping to zero in on the effects of that DNA on our bodies.

Now, a new study published in Stem Cell Reports takes things one step further by actually growing human brain tissue and then searching it for Neanderthal DNA. As it turns out, traces of early human-Neanderthal interactions have been waiting to be discovered all along.

For the study, which was led by J. Gray Camp of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Basel, used stem cells from a European biobank called the Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Initiative, or HipSci for short. The individuals that have submitted their genetic material to the program are largely based in the UK and Northern Europe, which scientists already know have a high density of humans that retain traces of their Neanderthal past.

Using the stem cell material, the researchers built tiny chunks of brain tissue called organoids. The tissue is human in origin, but it still contains up to 4% Neanderthal DNA. That might not seem like a lot, but when you combine that small percentage from each individual you eventually reach a point where you have a much larger percentage of Neanderthal genes to work with.

The brain bits were grown in a dish, but the DNA they hold could have real-world impact in the future. Understanding how Neanderthal DNA shaped human evolution could explain the origins of things like hair and skin color, while also teaching us more about how Neanderthals themselves lived. Building organoids using Neanderthal DNA could reveal things about the health, diet, and even cognitive abilities of the ancient people.