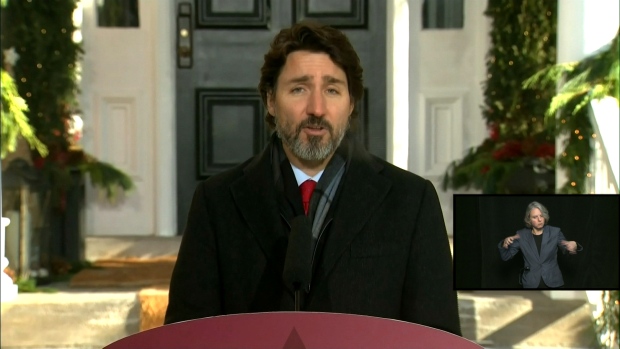

Justin Trudeau’s decision to shuffle his cabinet is the strongest sign yet that he could soon send Canadians to the polls.

The prime minister rearranged his front bench Tuesday when a key minister announced he is stepping down because he doesn’t want to run in the next election, which Trudeau may now have reason to expedite.

Trudeau’s approval rating surged last year after his government doled out some of the world’s most generous COVID-19 support programs to keep Canada’s economy afloat. That presents a window of opportunity for his Liberals to try to win back their majority in the first half of 2021 — especially if vaccination goes smoothly and the economic recovery stays on course.

The Liberals were held to a minority in 2019, forcing Trudeau to work with the opposition to pass legislation. Minority governments in Canada usually last about two years, and the prime minister’s response to the pandemic — spend fast and spend big — proved popular enough to give his party a modest lead in recent polls.

“If the ballot question is the handling of the pandemic, Trudeau is well-positioned to receive broad support from the Canadian public,” said Marcel Wieder, a former Liberal campaign adviser who now heads the Ottawa-based Aurora Strategy Group. “It’s going to be very challenging for opposition parties to frame an election outside of that.”

The cabinet shuffle saw Francois-Philippe Champagne moving to industry, Marc Garneau to foreign affairs and Omar Alghabra to transport. The changes came after Industry Minister Navdeep Bains decided to leave politics, and they’re aimed at shoring up Trudeau’s front bench ahead of any campaign.

Asked multiple times on Tuesday whether he wants a spring election, the prime minister told reporters his preference isn’t for one and that his main priority is to get the nation through the pandemic. But he wouldn’t comment when asked whether he would refrain from triggering a vote until then.

An election, whenever it comes, will help decide the future direction of a Group of Seven nation that was afflicted by low oil prices and plummeting immigration last year and relied on real estate, resilient consumer spending and soaring levels of government borrowing to keep its economy humming.

In his first term after his 2015 election, Trudeau broke with Canada’s decades-long political consensus in favor of balanced budgets, pledging modest deficits to support growth. COVID-19 amplified that, and the result was one of the biggest fiscal swings anywhere: from a shortfall of one per cent of gross domestic product to about 17.5 per cent.

How to get that deficit down is likely to be a major issue in any campaign. So is Trudeau’s ability to deliver on promises to bolster the country’s social system and fight climate change, including to dramatically increase a carbon tax that’s unpopular in the energy-rich west, where his political support is already thin.In the short term, though, voters may be focused on the economy and jobs. Canada’s economy was on course to shrink by about 5.6 per cent in 2020, compared with a 3.5 per cent contraction in the U.S., according to Bloomberg’s latest surveys of economists. That sets the stage for a slightly sharper rebound in the northern nation, which is projected to grow 4.4 per cent this year, compared with four per cent stateside.

The national mood is already improving. Consumer confidence has been rising steadily, ending the year almost exactly where it started — which was before COVID hit Canadian shores.

With vaccinations underway earlier than expected, Trudeau would also be in a stronger incumbent position than he was in 2019, when his party was mired in scandal and his personal image was marred by missteps on the world stage.

However, the prime minister’s path to regaining a majority isn’t without challenges. The margin between victory and defeat is thin and a campaign surprise could upend everything.

Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole is another wild card. Though he remains untested in federal elections, his military background and pledges of fiscal prudence could sway center-right voters.

“The Canadian economy was already showing serious signs of weakness before the pandemic hit,” O’Toole said in November. “Now, Justin Trudeau is running a historic deficit — and is still leaving millions of Canadians behind.”

Then there’s the state of global affairs. The inauguration of Joe Biden — who in promising the world “America is back” is borrowing a line Trudeau used upon taking office — will give the prime minister an ally in the U.S. on climate change. But he may have a tough time selling the new president on a crude-oil pipeline that’s a priority for western voters.

Trudeau will also have to show he’s up to the task of managing Canada’s second-most important trading relationship. With Canada’s arrest of a Chinese telecom executive on a U.S. extradition request in 2018, relations with China hit their lowest point since the prime minister’s father Pierre Trudeau established diplomatic ties five decades ago.

The question also remains whether voters will take kindly to an election before the end of the COVID-19 inoculation campaign, which health officials say could run until the fall. Any political party seen as forcing Canadians to vote in the midst of a pandemic could pay for it in the polls.

“Unless you have a situation where people are itching for change, there tends not to be strong appetite for an election,” said Shachi Kurl, president of the Angus Reid Institute, a polling agency. “Trudeau rolls the dice of an election at his peril.”