The World Health Organization has updated its ongoing guidance on COVID-19 medications to advise against using the antiviral drug remdesivir to treat hospitalized patients, no matter how severe their illness may be.

According to the update, published in the medical journal the BMJ on Thursday, current evidence does not suggest remdesivir affects the risk of dying from COVID-19 or needing mechanical ventilation, among other important outcomes.

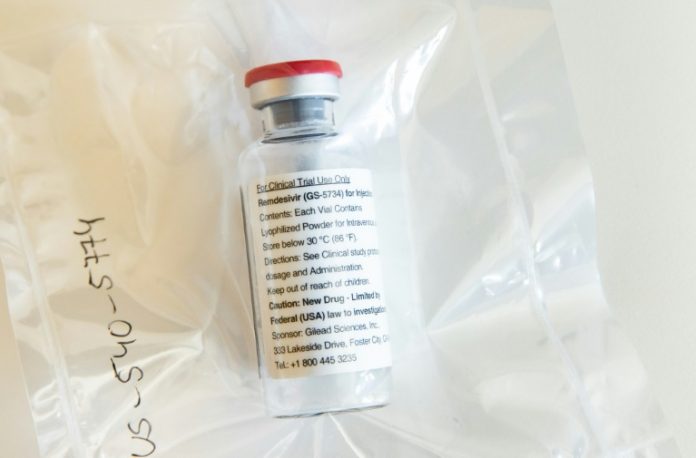

WHO’s new update comes about a month after the company Gilead Sciences, the maker of remdesivir, announced that the US Food and Drug Administration approved remdesivir for the treatment of coronavirus infection. The drug became the first coronavirus treatment to receive FDA approval. On Thursday, FDA gave emergency use authorization to a combination of remdesivir and the rheumatoid arthritis drug baricitinib to treat suspected or confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Remdesivir may have received FDA approval but not WHO’s recommendation because of emerging research, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, who was not involved in the WHO guidance. Studies initially showed some benefit against Covid-19, but as more data accumulate, that appears to be changing,

“We’ve seen people realize that the benefit of remdesivir is marginal at best — and the only benefit we had been touting was maybe it gets people better quicker. But the evidence base for that is weak, it’s not ironclad, and I think that’s what we’re seeing reflected in the WHO guidance, just more evaluation of the data that’s out there and more of now,” Adalja told CNN on Thursday.

“The fact that it was an antiviral that showed some benefit in certain trials — but not in all trials — was enough to push people to want to use it because we had no tools, but I do think it probably will be supplanted shortly,” Adalja said, adding that the indication for drugs can change over time.

“We have many FDA drugs approved for many conditions but are they always in the guidelines and always recommended? No, not necessarily. Not all of them. So, we are often refining treatments,” Adalja said. “Is remdesivir going to be a go-to drug? Probably not so much anymore.”

WHO convened an international panel of 24 experts and four survivors of COVID-19 to review data and make recommendations. The recommendation against remdesivir was based on data from four randomized trials including 7,333 people hospitalized with COVID-19.

“The panel concluded that most patients would not prefer intravenous treatment with remdesivir given the low certainty evidence,” researchers from various institutions around the world wrote in the updated WHO guideline.

“Any beneficial effects of remdesivir, if they do exist, are likely to be small and the possibility of important harm remains,” the guideline says. “They acknowledged, however, that values and preferences are likely to vary, and there will be patients and clinicians who choose to use remdesivir given the evidence has not excluded the possibility of benefit.”

Gilead Sciences, the maker of remdesivir, which is sold under the name Veklury, said in a statement Thursday that the antiviral has been recommended by other organizations and countries based on “robust evidence from multiple randomized, controlled studies published in peer-reviewed journals.”

“We are disappointed the WHO guidelines appear to ignore this evidence at a time when cases are dramatically increasing around the world and doctors are relying on Veklury as the first and only approved antiviral treatment for patients with COVID-19 in approximately 50 countries,” the company said.

Peter Horby, a professor in the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Medicine who was not involved in the update, referred to WHO’s updated recommendation as reasonable in a written statement on Thursday.

“Given this lack of evidence of any benefit on mortality, the risk of ending up on a ventilator or the time to clinical improvement, the World Health Organisation have reasonably recommended against the use of remdesivir in patients hospitalised with COVID-19, whatever their disease severity,” Horby said in the statement distributed by the UK-based Science Media Centre.

“Remdesivir is an expensive drug that must be given intravenously for five to ten days, so this recommendation will save money and other healthcare resources,” Horby said. “Remdesivir has been recommended in several COVID-19 treatment guidelines so this new analysis will necessitate a rethink about the place of remdesivir in COVID-19.”